The Base Layer

"The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise."

For Plato and his followers, the objects and phenomena encountered in the day-to-day world were lossy copies of hypothetical ideal-types, with the existence of such ideals being proven by the broad social agreement around words and their associated concepts. Thus, while no real object embodied perfect beauty, the fact that there was broad consensus when it came to ranking objects on a beautiful-ugly spectrum was proof that a perfected ur-beauty must exist somewhere, and - taking things a step further - have a hand in the structuring of its imperfect physical reflections:

We hold that all the loveliness of this world comes by communion in Ideal-Form. All shapelessness whose kind admits of pattern and form, as long as it remains outside of Reason and Idea, is ugly from that very isolation from the Divine-Thought. And this is the Absolute Ugly: an ugly thing is something that has not been entirely mastered by pattern, that is by Reason, the Matter not yielding at all points and in all respects to Ideal-Form. But where the Ideal-Form has entered, it has grouped and coordinated what from a diversity of parts was to become a unity: it has rallied confusion into co-operation: it has made the sum one harmonious coherence: for the Idea is a unity and what it moulds must come into unity as far as multiplicity may.[1]

The classical Daoists held the opposite perspective. They argued that conventional categories (beauty, tree, human) were useful as fiat tokens for everyday interaction but a poor reflection of the underlying truth. They agreed with Plato that physical entities were shaky and temporary instantiations of something bigger, but this bigger phenomenon was - rather than a word and its associated concept - the abstract and indefinable forces that produced them. Beauty is not a primum mobile, but simply a fleeting manifestation of the evolutionary pressures that define it.

Duke Huan, seated above in his hall, was (once) reading a book, and the wheelwright Bian was making a wheel below it. Laying aside his hammer and chisel, Bian went up the steps, and said, 'I venture to ask your Grace what words you are reading?' The duke said, 'The words of the sages.' 'Are those sages alive?' Bian continued. 'They are dead,' was the reply. 'Then,' said the other, 'what you, my Ruler, are reading are only the dregs and sediments of those old men.' The duke said, 'How should you, a wheelwright, have anything to say about the book which I am reading? If you can explain yourself, very well; if you cannot, you shall, die!' The wheelwright said, 'Your servant will look at the thing from the point of view of his own art. In making a wheel, if I proceed gently, that is pleasant enough, but the workmanship is not strong; if I proceed violently, that is toilsome and the joinings do not fit. If the movements of my hand are neither (too) gentle nor (too) violent, the idea in my mind is realised. But I cannot tell (how to do this) by word of mouth.[2]

And based on the evidence we have, the Daoists have probably won this one. Not only are the mundane trees we interact with not a reflection of a divinely perfect tree-form, but phylogenetically they do not exist at all. An elm tree is closer to a strawberry than a pine, and with each new generation the limits of what can be considered elm- or pine-like change slightly. What is real are the evolutionary forces that push certain plants to take on more or less tree-like forms.

For the original Daoists, these underlying trends were impossible describe in words, not so much for mystical reasons as practical ones: every phenomenon is the product of interactions between multiple other mutually reinforcing and contradictory forces. You can’t say that “the Dao is x”, because this necessarily implies the simultaneous presence of x⁻¹ and thus proves your own description at best inadequate and at worst plain wrong. It is impossible for one individual to embody the Dao, for the same reason that it is impossible for one individual to embody a football match. The wheelwright’s skill is meaningless without the resistance of the wood to being transformed. Nevertheless, it is still possible for a single individual to get a sense of the Dao’s general features by repeated experimentation:

His cook was cutting up an ox for the ruler Wen Hui. Whenever he applied his hand, leaned forward with his shoulder, planted his foot, and employed the pressure of his knee, in the audible ripping off of the skin, and slicing operation of the knife, the sounds were all in regular cadence. Movements and sounds proceeded as in the dance of 'the Mulberry Forest' and the blended notes of the King Shou.' The ruler said, 'Ah! Admirable! That your art should have become so perfect!' (Having finished his operation), the cook laid down his knife, and replied to the remark, 'What your servant loves is the method of the Dao, something in advance of any art. When I first began to cut up an ox, I saw nothing but the (entire) carcase. After three years I ceased to see it as a whole. Now I deal with it in a spirit-like manner, and do not look at it with my eyes. The use of my senses is discarded, and my spirit acts as it wills. Observing the natural lines, (my knife) slips through the great crevices and slides through the great cavities, taking advantage of the facilities thus presented.[3]

Thus the texts effectively say that while the phenomena they wish to talk about are impossible to describe in the first-order natural language vocabulary available to them, they can nevertheless be approached, recognised and wordlessly understood via experimentation in specific practical activities - whether making wheels, cutting meat, leading an army or ruling a state. The resistance they encountered in doing these things and the methods they learnt for responding to it were probably universal or the next thing to it. Thus, by putting all one’s effort into learning the Dao of calligraphy, government, or burglary, one may thereby be vouchsafed a glimpse of the processes of processes that constitute the underlying universal Dao, even though your language would still lack the levels of abstraction necessary to describe them effectively. A good king would share few skills with a good chef, but the lessons learnt as a byproduct of acquiring those skills would be broadly the same - the problem being that the years of study required to realise this would mean that each would only ever have time to understand these principles as they related to his own field. Thus the underlying processes of processes tend only to be described in detail insofar as that they relate to a given field, with students being expected to extrapolate silently and reason by wordless analogy to arrive at universal applications.

The result of all this was an understanding that their true object of study lay in meta-processes, and that a higher level of abstraction than was possible in natural language would be required to describe them precisely, but no significant effort was made to invent a formal vocabulary that would be capable doing so. Indeed, the original Daoist thinkers seem to have preferred to do without a specialist technical vocabulary, probably - counter-intuitively - as a means of preserving the ideas themselves within a primarily oral transmission. Hinting at a deeper truth would provoke genuinely dedicated students to investigate for themselves and develop a true understanding rather than merely memorising lists of words for the test. Instead, they simply said “you’ll know it when you see it” and encouraged students to go out and experiment.

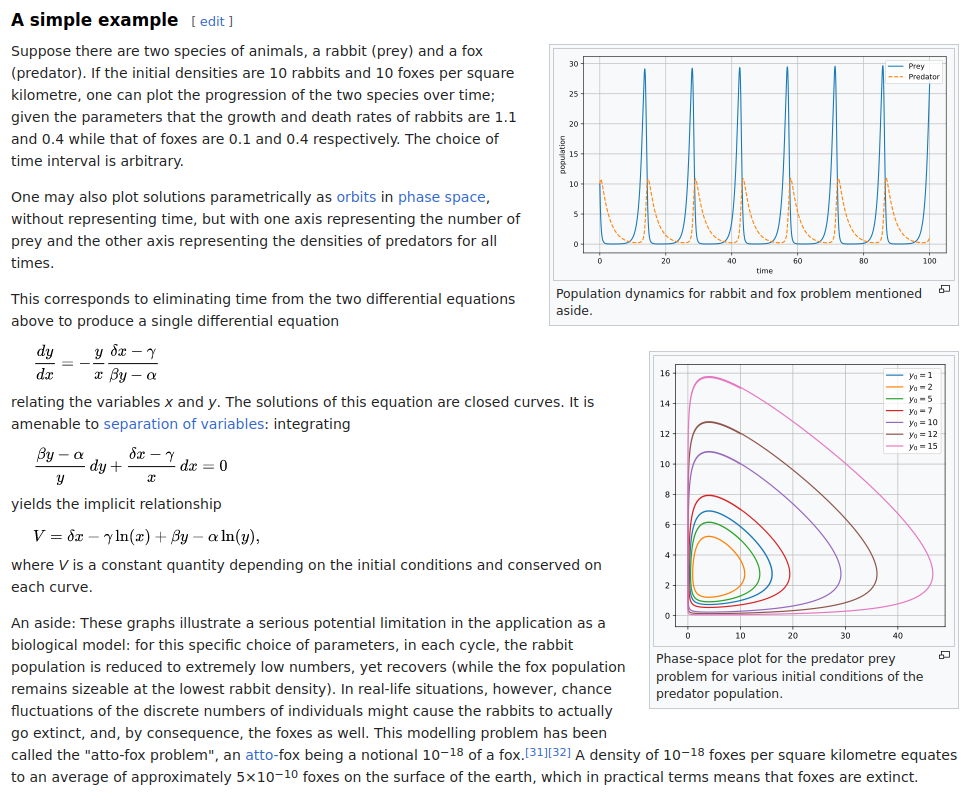

We took a step forward in the quest for descriptions that are both precise and realistic with the development of differential calculus and formal probability theory. Suddenly we could describe not just processes but processes of processes. Simultaneously, we gained the ability to describe vagueness precisely. Phenomena that had once been esoteric-bordering-on-mystical suddenly became a rather dull component of every high schooler’s daily grind.

Which is great, but we’re still not at Zhuangzi’s desired level of abstraction yet. We didn’t really begin to approach this until the 20th century:

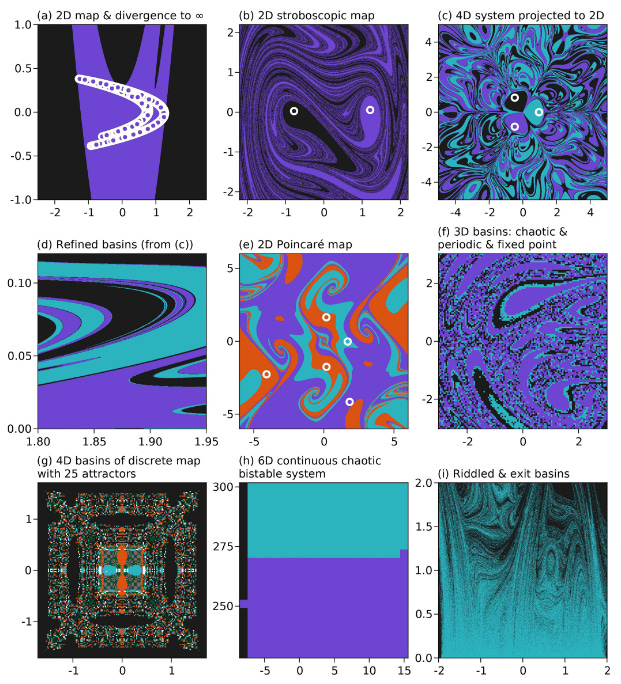

With phase space plotting we can say precisely that a large number of rabbits is good for the fox population at t1 and bad for it at t2: the Dao of predation is thus both x and x⁻¹ depending on the time frame under consideration.

Or, as the Huainanzi has it:

There once was a father, skilled in divination, who lived close to the frontier. One of his horses accidentally strayed into the lands of the Xiongnu, so everyone consoled him. The father said, “Why should I hastily conclude that this is not fortunate?” After several months, the horse came back from the land of the Xiongnu, accompanied by another fine horse, so everyone congratulated him. The father said, “Why should I hastily conclude that this is not unfortunate?” His family had a wealth of fine horses, and his son loved riding them. One day the son fell off the horse, and broke his leg, so everyone consoled the father. The father said, “Why should I hastily conclude that this is not fortunate?”One year later, the Xiongnu invaded the frontier, and all able-bodied men took up arms and went to war. Of the men from the frontier who went, nine out of ten men perished. It was only because of the son's broken leg, that the father and son were spared this tragedy. Therefore, misfortune begets fortune, and fortune begets misfortune. This goes on without end, and its depths can not be measured.

It is not always easy to tell whether these ideas are difficult to express because they are hard to imagine or hard to imagine because they are difficult to express. Certainly not all of them require Very Hard Maths, and still we struggle, suggesting that this may not be the barrier to entry. Humanity has been practicing artificial selection for millennia and yet the idea that other animals may be doing it to one another in the wild did not occur/catch on until Charles Darwin published On The Origin of Species in the 19th century. Why?

A few days ago, a poster called cyriakharris blew Twitter’s mind by pointing out that Lego blocks will not only self-assemble if placed in a bag in a washing machine, but that unstable configurations will disintegrate and reform until stability is attained:

You might say “Well obviously his audience is impressed, Twitter is full of dumb people”, but mathematicians periodically have venomous arguments about whether assembly theory (which essentially says that if you chuck Lego blocks into a washing machine they will self-assemble into increasingly stable configurations, and was formalised in 2017[4]) is or deserves to be a thing, which are essentially expressing the same astonishment expressed in longer words.

In other words, we’ve come both a very long way and not very far at all since the redaction of the Dao De Jing, depending on your perspective. We have a lot more layers of abstraction at our disposal, and can describe high-level processes with a level of precision that the Daoists 2300 years ago never dreamed of. Nevertheless, we remain haunted by the - correct - suspicion that they are still insufficient to allow us to express what is actually going on.

The main difference is that we’re doing our damnedest to wrap words (or numbers) around our quest for higher levels of precise abstraction. We may not be there yet, but we kind of know where there most likely is:

It has a lot to do with algorithmic complexity;

Ditto entropy/time;

Ditto feedback mechanisms and evolutionary processes;

You only really start to notice it once you’re in deep in a particular domain, even though the exact same principles seem to underlie most/all fields. (Processes of processes of processes?)

The result is that while we’re pretty sure that there are Big Important Ideas happening out there somewhere, we are only really capable of parsing them through our specific intellectual silos. In the words of Meaningness:

Cybernetics was quite heterogenous – it included Margret Mead as well as Claude Shannon – and the pieces didn’t really fit together well. There was an exciting sense of a possibility of synthesis that turned out not to be feasible. The works of those two, for extreme examples, are radically incommensurable. The various pieces went off in different directions and got called different things. The original antiaircraft-gun approach of Weiner’s turned into control theory, which is a normal, boring, sometimes important branch of engineering mathematics. The Bateson/Mean approach turned into “complex systems theory”, which points at interesting phenomena but seems not to have much of substance to day about them. The neural modeling stuff (McCulloch and Pitts) turned into “connectionism” and then “deep learning” and then ChatGPT. The mind-modeling stuff turned into GOFAI. Information theory was very exciting but it turned out that Shannon had done everything that it was possible to do. (Minsky often told the story about how he was on the program committee for the Second International Conference on Information Theory, and they called it off because there were no new results, and it was pretty clear there never would be any new results.)

Granted, it’s not all down to the universe doing the dance of the seven veils with us. A good chunk of the problem can probably be blamed on academic territorialism. The maths guys tend to look down on my agent-based models as borderline-moronic truisms, while I regard complex systems theory as a once-respectable domain that has fallen to the kind of business authors who’ll show you a Lorenz attractor and tell you to run your marketing department like that. Moreover, the fact that so much of the content belongs to multiple disciplines means that it is often owned by none, and the splitting of relevant material across different fields makes piecing together a coherent theory of all of it even harder. L-systems are a good example of this - they belong to every field and none, and while they seem to have something big and important about the way the world works, their main practical application is for procedurally generating trees in video games. Thus they are incredibly interesting but also so obscure that Stephen Wolfram was able to come up with the idea independently a few years back and get excited enough to announce that his team had solved physics. You can find hordes of frustrated high school students on Quora desperately trying to work out what exactly they should major in to have a chance of getting a look at some information theory before they’re 30 (unexpected pro-tip: political science - you won’t get any help, but no one will go out of their way to prevent you).

The fundamental problem, however, seems to be the same as that experienced by the early Daoists: you can only really get close to the underlying truth via a lifetime of effort in a particular domain. Indeed, brilliance can be an active detriment in the process, since brilliance encounters less resistance than plodding determination and tends to be less inclined to reform itself. Thus it may learn more about the specific target subject but less about the universal processes that structure its interactions with it, only really discovering the latter once it reaches the limits of its own inherent genius. Whatever’s going on in the base layer, it is hard to see until you’ve gone pretty much as far as native intelligence can carry you in your own domain, meaning that - given the time constraints, it is essentially impossible for any human to get a transversal view.

Impossible for any human, perhaps, but not necessarily for any entity. Deep neural nets are designed specifically for the purpose of encountering failure and improving themselves as a result. They are great at spotting connections across multiple disparate data-points and aren’t necessarily limited to a single human lifespan in which to do it. Moreover, because they are models rather than statements, they are entirely capable of describing dialectic phenomena accurately and completely. A Daoist writing in 400 BC is constrained by language to say either y = x or y = x⁻¹ and even a phase space model has is constrained by its time dimension. A neural network can express both at the same time, declining each in function of the precise triggers that induce it. In other words, a model is not a simple description, but a compressed and interpretable parallel universe. This means that we can use them to do things like this:

The Theory of Everything, when it comes, probably won’t be a series of equations (granted, I haven’t checked all of it yet, but it seems like there’s sufficient indication that everything just doesn’t work like that), but it might be a whitebox neural network - a replica universe capable of explaining itself to us and maybe allowing us to talk back.

[1] Plotinus, An Essay on the Beautiful.

[2] Zhuangzi, The Way of Heaven. Or, as Voltaire put it, “Ask a toad what beauty is, the to kalon? He will answer you that it is his toad wife with two great round eyes issuing from her little head, a wide, flat mouth, a yellow belly, a brown back.”

[3] Zhuangzi, Nourishing the Lord of Life.

[4] Or possibly by Christopher Smart during a bout of insanity in the mid-18th century: “For Resistance is not of GOD, but he — hath built his works upon it… For Attraction is the earning of parts, which have a similitude in the life.”